Under the Auspices of AMHF: Early Identification and Prevention of Psychotic Disorders in Children and Youth

by Evander Lomke on

What follows is the up-to-the-minute report on the fundamental research project of AMHF and Astor Services for Children & Families

20-month Progress Report – June 9, 2014

Project Goal

To design and implement an evaluation and intervention program for both children and adolescents at risk for psychotic disorders and their families. Youth identified as at risk for psychotic disorders from the initial assessment and who meet criteria after an in depth evaluation and diagnosis procedure, later chose (with their caregivers and treatment providers) and initiated during a consultation session a customized treatment plan offered from a menu of evidence-based interventions. Initial screening, evaluation, and treatment outcome data are provided to illustrate the current status of the project and the remaining steps to complete the project are discussed.

Care as Usual (CAU)

Children and youth receiving services in Astor’s treatment programs typically participate in a standard initial assessment during which information about their needs and strengths is used to formulate a care plan. A wide range of activities can be targeted in the care plan, including interventions related to psychotherapy, skills training, medication management, and case management, and sometimes care plans can include childcare, recreation, physical healthcare, and special education where relevant. A clinician performing the initial assessment has, at most, 90 minutes to meet the family and youth for the first time, identify treatment needs, and formulate a care plan that addresses the presenting problems. The Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths – NY (CANS-NY) is used as a treatment planning and outcomes measurement tool. It is a structured assessment widely used by professionals working with children and youth around the world, and evaluates child/youth and family strengths and needs across broad domains: Child/Youth Strengths, Primary Caregiver Strengths, Primary Caregiver Needs, Child/Youth Life Functioning, Child/Youth Risk Behaviors, and Child/Youth Behavioral Health. However, specialized and evidence-based assessment protocols to identify youth at risk of psychotic episodes are not utilized. In many of Astor’s programs, the types of available intervention and treatment options are limited and most offer limited family involvement in treatment and care. The standard treatment package across programs includes individual and/or group and/or family therapy, psychiatric evaluation and medication management if needed, and in certain programs, educational services.

Clinicians working within the structure of these programs have little opportunity to use the assessment data they collect to screen youth for risk of developing specific problems (such as psychosis) and conduct further comprehensive evaluations with individual youth that present with these concerns. The types of interventions that are most effective with these youth – those that are collaboratively planned with families, coordinate care provided across multiple settings (e.g., the home environment, school, therapy office, psychiatrist’s office), and are focused on building skills for optimal functioning – are infrequently delivered.

Enhancement of Care as Usual (CAU) AMHF Youth

The AMHF project provides the opportunity to augment substantially care for youth that need it the most – youth at risk for psychotic episodes. Using the standard initial assessment procedures to screen youth for psychosis and risk of psychosis, we invite the identified youth and their families to participate not only in an enhanced assessment and consultation service, but also in specialized treatment protocols. There are three unique areas of benefit for the youth participating in the AMHF project. First, we evaluate youth in depth. We spend more time than is possible in Care as Usual (CAU) with youth and their families to provide a comprehensive assessment using structured and specialized evaluation tools developed and used by experts in early psychosis. The evaluation procedures we use allow us to pay attention to issues that might be missed in CAU, such as specificity of symptoms, diagnostic complexity, and barriers to accessing potentially helpful interventions. Second, we offer in consultation with families and care providers a more fine-grained understanding of the unique youth, which allows us to place youth on a path to receive individualized evidence-based interventions. Third, over time we systematically measure impact on youth functioning, assist with implementing the interventions planned, and continue to evaluate outcomes in a seamless process.

Current status of the AMHF project:

From the time funding began in October of 2012, the project was staffed, the research design approved, the Screening and Comprehensive Evaluation procedures and the Consultation menu of evidence-based interventions were developed. Staff training on the structured interview protocol was completed and by June 2013, hundreds of Astor youth were screened for psychosis risk. Participant recruitment began in March 2013, Comprehensive Evaluations began in April 2013, and the first Consultation meeting was held in May 2013, with follow-up data collection beginning in June 2013. Now in its second (unfunded) year, participant enrollment has been closed. All Evaluations were completed as of January 24, 2014 and Consultations were finished as of March 2014. Outcomes for all 13 AMHF youth will be tracked for one year post-Consultation, so that the last follow-up data collection will occur in March 2015.

Participant Enrollment

Since April of 2013, 14 at risk youth and their families have enrolled in the AMHF project. One youth dropped out of the project because of an unanticipated discharge from Astor, making a total of 13 currently enrolled AMHF youth expected to complete all phases of the project. We have completed comprehensive evaluations, consultations, and have begun providing ongoing technical assistance and care coordination with all 13 AMHF youth. In addition, all have participated in at least one formal follow-up call with a member of the research team to evaluate treatment outcome and provide assistance in implementing the treatment plan. The first youth who was enrolled recently completed participation in the project, as the 12 months of regular follow-up contact with the family concluded in mid May 2014. By the end of August 2014, six more youth will finish and in the Fall and Winter months follow-up up contact will continue with the remaining six enrolled youth. The project will officially come to an end in March 2015, at which time marks a full year of follow-up contact with the 13th and final youth who participated in evaluation, consultation and follow-up phases.

Evaluation of Psychosis Screening Procedure

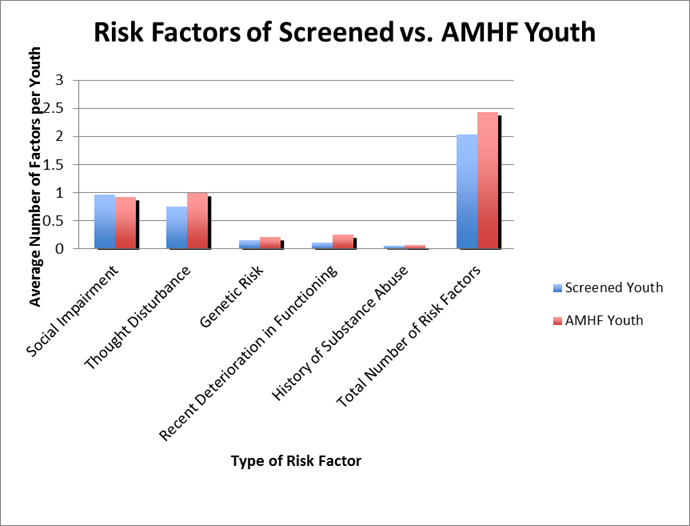

To assess how the 14 enrolled AMHF youth are similar or different from youth receiving services in Astor’s other treatment programs, we compared three distinct groups: (1) 14 enrolled AMHF youth, (2) 67 at risk youth who met the initial assessment criteria but not the in depth evaluation and diagnosis criteria to be enrolled in the AMHF project (the Screened youth), and (3) the general population of Astor youth (the Astor youth). Through the standard assessment procedure, we identified 81 youth whose presenting problems warranted more extensive evaluation for risk of psychosis, of which 14 youth were enrolled in the AMHF project and 67 were considered Screened, but not enrolled. Youth were considered to be at risk for psychosis if they had at least two of the risk factors (Genetic risk, Thought disturbance, Recent deterioration of functioning, Social impairment, and Substance abuse). The mean number of risk factors for psychosis for AMHF youth was 2.43 whereas for Screened youth it was 2.04, indicating that those youth who were enrolled in the study showed greater risk.

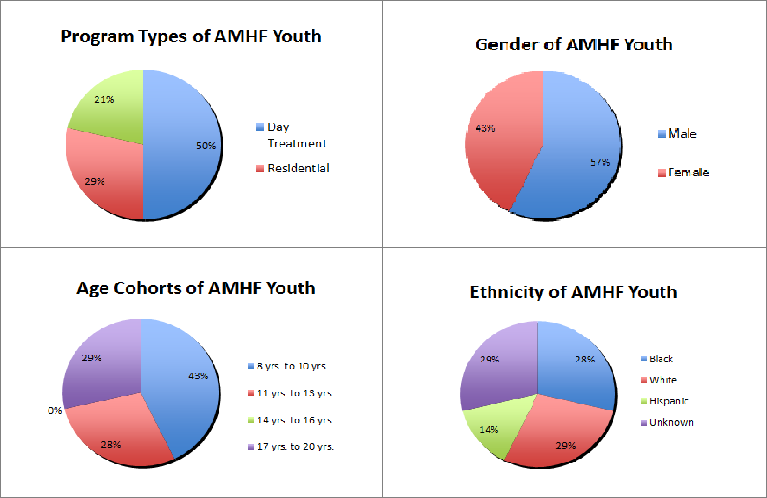

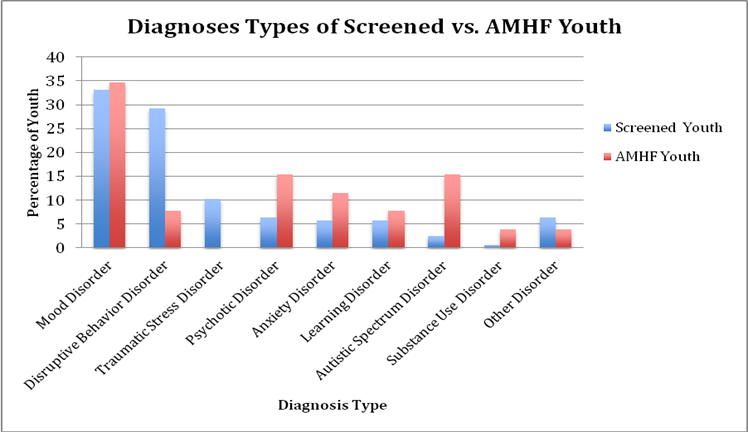

In the charts on the following page, similarities and differences between the three groups of youth are shown regarding gender, age ranges, ethnicities, the program types in which youth receive care, and the diagnoses they had at the time of screening.

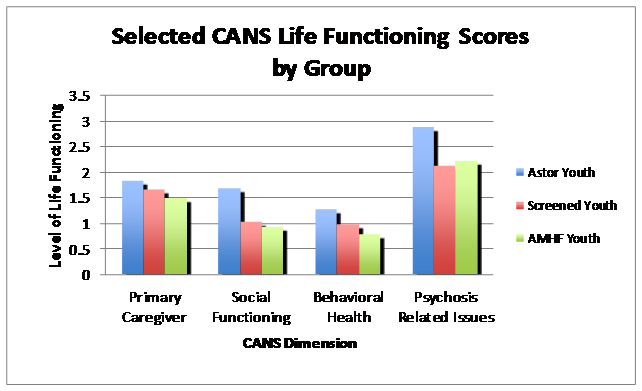

With the intent of highlighting the differences and similarities among the three groups, we provide some data from the Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths (CANS) used for the screening. Specifically, CANS items used for screening purposes were chosen based on their similarities to the risk factors known in the literature to predict conversion to full psychotic disorders in youth. Items assessing symptoms of Psychosis, Substance Use, and impairment in Social Functioning were selected.

In the chart below, CANS scores range from 0 to 3 such that higher scores indicate better functioning. As illustrated in the following charts, the AMHF youth generally evidenced lower functioning compared to the other groups, especially in behavioral health. These data suggests that the screening procedures appropriately identified youth with psychosis risk. It also illustrates that the CANS does not adequately differentiate among youth at risk for psychosis – note that the scores for the Screened and AMHF youth were essentially the same. Hence, a more in-depth evaluation and diagnosis is warranted to identify effectively youth at risk for psychosis.

Enhancement of Care as Usual (CAU) for AMHF Youth

As discussed above, the AMHF youth received an enhanced service package including comprehensive evaluation, consultation in collaboration with families, evaluators, and care providers regarding best practices, and continued support to encourage implementation of evidence-based interventions. Ongoing measurement of the impact of this enhancement of Care as Usual (CAU) will help to fine-tune this package, resulting in improved care for all participants.

In the interest of illustrating in detail the enhancement of CAU that comes with project participation, here is an example of a youth and family’s experience of the project from the time of enrollment through evaluation, consultation, and follow-up:

The family and researcher meet to discuss the project and obtain informed consent, and are joined by the youth upon family approval. The youth is accompanied by his clinician at the day treatment program he attends, and the clinician sits down with the researcher, family, and youth, to participate in a discussion about what happens during the evaluation, the consultation, and afterwards. Family and youth discuss how participation might be beneficial and agree to proceed with the evaluation. The researcher meets with the youth and family, together, and separately depending on clinical judgment, over the course of the two-session evaluation. During each two-hour session, the researcher gets to know the youth and family, and asks structured questions to assist in diagnosis and evaluate psychosis risk. Questions cover a variety of things – experiences, symptoms, strengths, and goals, and multiple sources provide information. After the evaluation is complete, a meeting is scheduled for the Consultation. The youth and family attend this meeting, which takes place a few weeks after the evaluation is complete. It is a meeting where the youth will recognize several different people in his life – his family, his therapist, the psychiatrist, and the evaluator. During the meeting the evaluator talks about what was learned during the evaluation, taking care to describe both needs and strengths, and present a thorough understanding of the youth as a person and the areas in which he struggles. Next, the evaluator discusses recommendations – using a menu of best practices with evidence-based treatments for the youth’s particular problems. Everyone in the room talks about the options for interventions and decides on a plan of care. About a week later, a written version of the plan developed during the meeting is distributed to the family and treatment providers. Then, his treatment providers and family start doing some of the things that were planned. The researcher follows up with the family, youth, and treatment providers at 1 month, 2 months, 4 months, 6 months, 9 months, 12 months post-consultation to see how the youth is doing, how things are going with the plan, and what help still is needed. When the care providers ask for information and resources to implement the interventions recommended and planned, the research team provides what is needed to move the plan forward. Upon the completion of one year post-consultation, the researchers conclude follow-up contact with the family and encourage them to seek out providers for any ongoing care coordination that is needed.

The Consultation: Evidence-Based Interventions Recommended for AMHF Youth

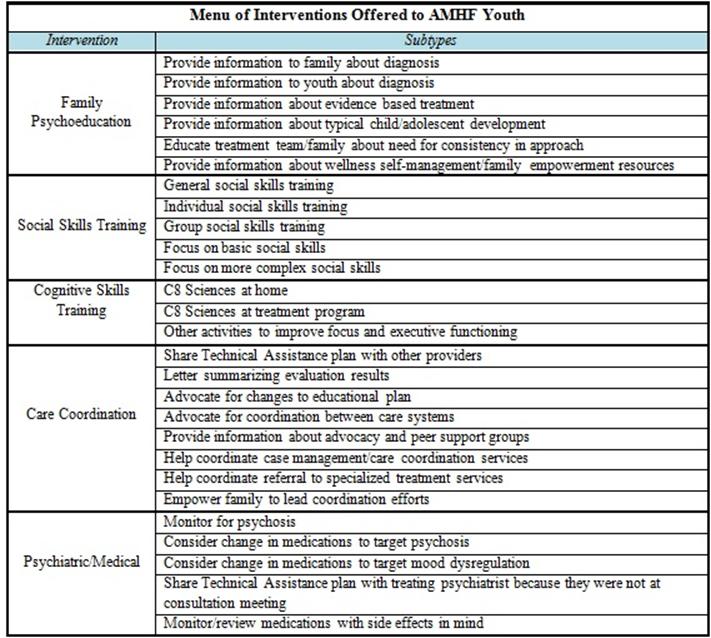

During the Consultation session, family members, youth, and care providers learned about and chose from a menu of evidence-based interventions. The interventions offered were selected based on research around the prevention or reduction of psychosis and included psychoeducation for families, social skills training, cognitive skills training, care coordination services, and specific recommendations regarding psychiatric and medical care. Family psychoeducation involves providing information to youth and families about diagnosis and the importance of problem-solving skills, coping skills, and family well-being. Social skills training is individual, group, basic, or complex skills training that aims to improve verbal and nonverbal behaviors involved in social interactions. Cognitive skills training, or cognitive remediation, involves activities designed to improve focus, attention, and executive functioning abilities. Care coordination is assistance with coordination and communication between care systems. For the purposes of this project, psychiatric and medical interventions are defined as recommendations to monitor current medications or consider a change in medications to target specific symptoms.

An example of Family psychoeducation includes providing information to a family member about the youth’s diagnosis. For instance, a family member with a stigmatizing view of mental illness could receive information about the youth’s diagnosis. This would be done in the hopes that learning about the illness and correcting misconceptions about it, the relationship between the youth and the family member would improve, and furthermore the family member might change his or her behavior toward the youth to be more supportive or helpful, resulting in improved functional outcomes for the youth.

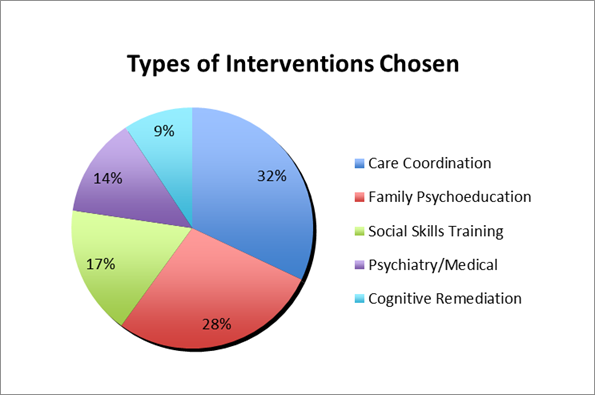

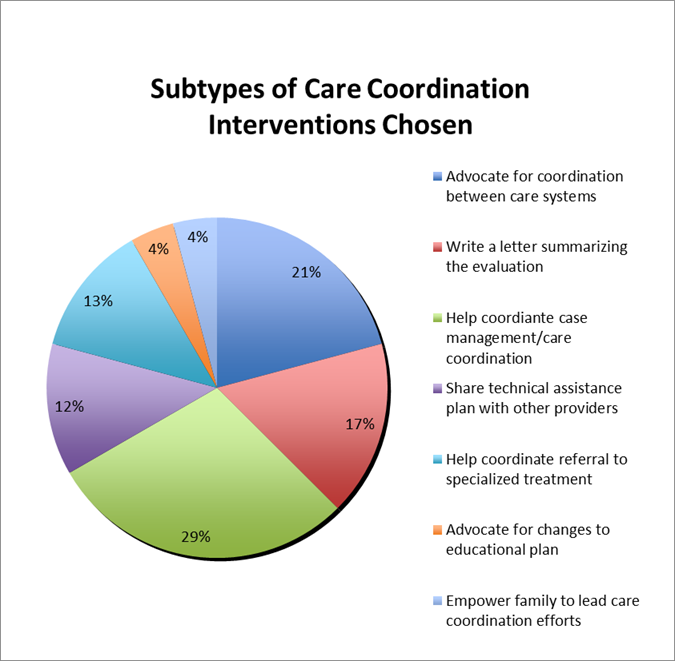

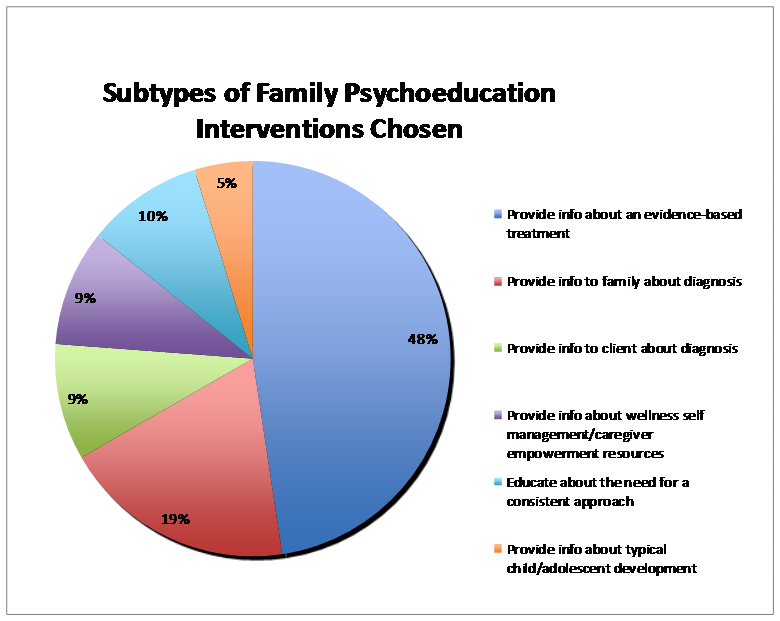

Depicted in the chart below is the percentage of instances that the different types of interventions were chosen by the family and treatment providers. See Appendix A for a description of intervention types and subtypes. See Appendix B for charts showing the frequency of Care coordination and Family psychoeducation subtypes.

It is evident that Family Psychoeducation and Care Coordination were most frequently integrated into the care plan developed during the consultation. These two areas are very important components of the enhancement of CAU being studied in this project. They are also the most complex of the intervention types because the actual tasks are highly individualized for each youth. These are evidence-based interventions that families and care providers are interesting in receiving.

Discussion of Short-term Functional Outcomes for AMHF Youth

Many areas of functioning are covered during follow-up contacts with families after the Consultation session takes place. A snapshot of the AMHF youth’s functioning in the following areas provides a view into the potential impact of AMHF project participation – behavior in school, social functioning in school, behavior at home, need for supervision at home, risky behavior at home, relationship with caregiver, changes in problem behaviors identified during the evaluation, overall social impairment, and overall functioning. To collect information about these areas of functioning, families are asked at each follow-up contact to give examples of how youth are doing in each area, and they are encouraged to comment on the specific ways the youth appears to have improved, gotten worse, or stayed the same since the previous follow-up contact. Therapists give some information about how youth are doing and what interventions they are receiving, and medical records are also reviewed as part of follow-up data collection.

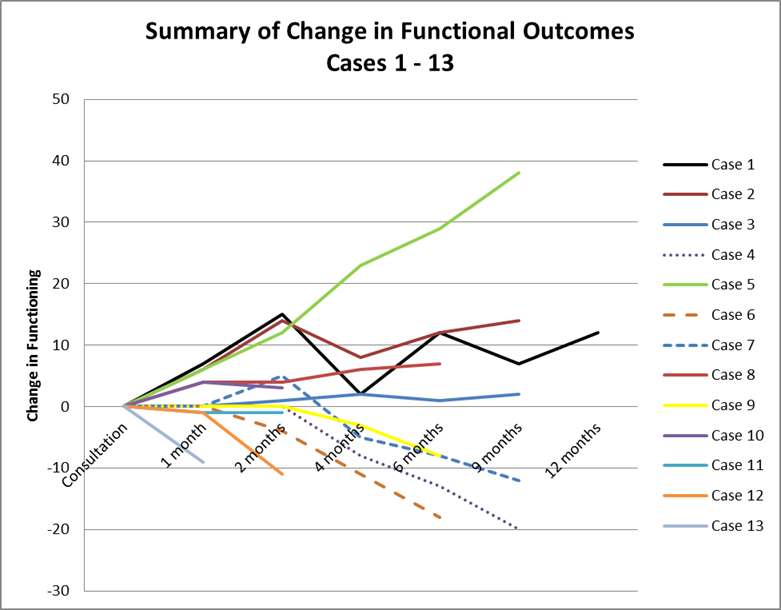

It is important to note that some AMHF youth have not been in the project long enough to have this level of data, and will continue to be followed at multiple time points post-Consultation (including at 6 months, 9 months, and 12 months). See the graph below for a summary of functional change in the 13 AMHF youth who have had at least one follow-up contact.

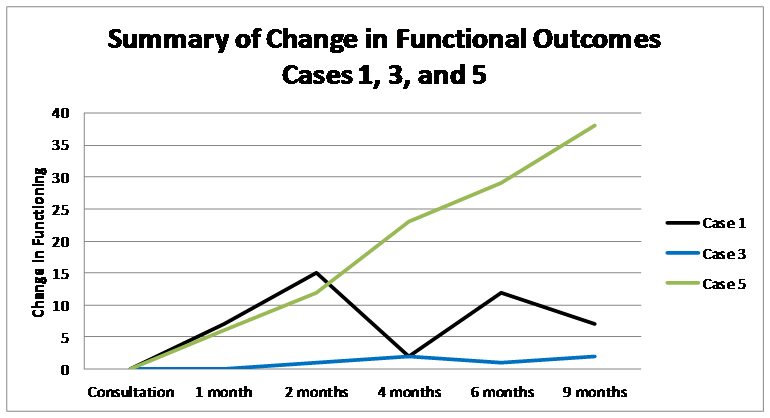

Depicted in the graph on the following page is the change over six time points for three of the AMHF youth for whom rich follow-up data are available. Overall functional change in a mostly positive direction is evident here.

One AMHF youth, Case 3, shows a pattern of gradual slight improvement and maintenance of this level of functioning over time. Another AMHF youth, Case 1, appears to have rapidly improved over the first two months post-Consultation, but then rapidly deteriorated by four months post-Consultation, improved again at six months post-Consultation, and then slightly deteriorated at nine months post-Consultation. Moreover, a third AMHF youth, Case 5, has demonstrated significant, continually improving functioning over the nine months since Consultation; more detailed information about this youth’s progress follows later in this report. Although they evidenced different trajectories to improvement, at nine months post-Consultation all three of these youth were functioning better than they were at the start of the project. The very different patterns of functional change in these three AMHF youth necessitate a more detailed look at what changes took place. See the next page for discrepancies between different areas of functional change for Case 1.

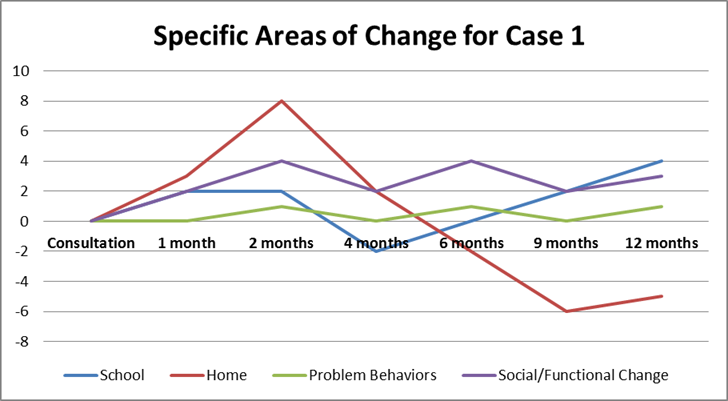

There are often ups and downs along the path of recovery for youth with significant behavioral health needs and the case above shows this tendency. During the first two months post-Consultation, gradual improvement in functional outcomes was reported at home and in school, with problems identified during the evaluation, and in overall. However, at the four- month follow-up the youth experienced a deterioration in functioning both at home and at school. To understand this deterioration, the four-month follow-up occurred about one week after the start of the new school year — this is a stressful time for many youth and their families, and in particular for youth struggling with severe emotional and behavioral concerns. However, problem behaviors identified during the evaluation and overall functioning showed a more gradual deterioration than did functioning at home and at school at the four-month follow-up.

Between the four-month and six-month follow-ups, interventions for this youth were adjusted for these stressful times; specifically, the youth’s educational plan was modified to resemble more closely the recommendation made during the consultation. Functioning at school then started on a trajectory of improvement, but it is clear from the graph that changes made at school were not associated with improvements at home. In fact, it was around this time that the youth was discharged from the in-home therapy services that had been in place when the family enrolled in the AMHF project. Without these supports in the home the youth’s functioning in that setting deteriorated. Recent follow-up contacts with the caregiver and outpatient therapist suggest that the youth’s struggles at home continue to be a focus of the care plan. It is important to consider the significant challenges inherent in coordinating care among different settings in which the youth functions (i.e., school, home, therapy). Care coordination with those providing educational services for youth is an area of the intervention that we have worked to strengthen in Year 2 of the project.

Barriers to implementing planned evidence-based interventions were also evident in the case of another AMHF youth who struggled to function well at school and at home. The school needed to cooperate with the family and with treatment providers to modify the care plan to address the youth’s psychiatric and educational needs identified during the evaluation. This collaboration among the family, researchers, and treatment providers helped the youth access appropriate interventions that would have otherwise not been available. As is clear in the chart on page 9 of this report showing functional change for three AMHF youth with rich follow-up data, this youth (Case 5) has made demonstrable improvements in overall functioning. At the time of the previously submitted 16 month progress report, informal follow-up contact with the providers and family had suggested that the intervention was successful and the family benefited from a combination of support and empowerment that was a direct result of the intervention and services offered through the AMHF project. Recently collected follow-up data revealing the youth’s improvements are consistent with initial reports and also indicate that the youth’s care providers are following the recommendations made during the Consultation regarding modifications and skill building to take place in the home, school, and treatment settings. Follow up contact between the research team and the youth’s caregiver has been focused on empowering her to communicate with providers about appropriately challenging the youth to build even more skills considering the great progress shown in last nine months. In Year 2 of the project, we have continued to provide resources to help overcome barriers and promote investigating in detail the project’s efficacy on the symptoms and functional outcomes for this and other AMHF youth.

One of the most commonly cited barriers is the lack of sufficient time to implement the interventions in the collaboratively developed care plan. Another barrier was the lack of availability of a chosen intervention. For example, several AMHF youth were recommended but were unable to participate in a social skills group. This type of group involves a trainer providing direct instructions on specific skills, facilitating modeling or role-play rehearsal of the skills, and giving the youth positive corrective feedback on their actual behavior. There are few, if any, good social skills groups available because of the dearth of adequately trained clinicians to facilitate them. Implementing this type of intervention is less likely to occur without availability and sufficient time.

If we were to receive outside funding to continue the project beyond Year 2, there are many areas where we could improve the protocol and therefore make it possible for youth at risk for psychosis to benefit from the interventions recommended. Several of these are described above in this report. Prioritized areas of improvement to the protocol are 1) Engage potential AMHF youth in the project via coordination with Astor family advocates; 2) Increase access to the highly effective interventions recommended to AHMF youth for example by supporting clinicians with the training resources they need to implement social skills training groups; and 3) Enhance collaboration with the professionals working with AMHF youth in their schools in order to more effectively coordinate care provided in these settings (e.g., provide psychoeducation to teachers about the youth’s needs and effective interventions to address psychosis in the classroom).

Because several families are in their final months of participation, our staff asked for their feedback inquiring specifically about what they found most helpful about their involvement in the project. Families have reported that receiving diagnostic clarification and information about evidence based treatments were positively experienced, in addition to the project’s collaborative stance with caregivers and clinicians to help navigate the complex systems of care serving these youth. For example, one of the care coordination activities in highest demand was for project staff to advocate with the committees of professionals tasked with making decisions about appropriate services and placements for AMHF youth considering the diagnoses of serious psychiatric illness. Starting in June 2014, as we continue to collect follow-up data on the progress made by AMHF youth who are still involved in the follow-up phase of the project, we will analyze the data and begin writing a monograph summarizing what we have learned about the implementation and short-term impact of the service under study. In final report on our findings we will analyze the more in depth information about AMHF youth functioning gathered at 6 months and 12 months post-Consultation. It will be particularly useful and informative to analyze the data collected via the CANS-NY to evaluate change in project participants. Upon the conclusion of the project we will include a full report on our findings in the monograph we anticipate completing in Winter 2015 – 2016.

A great deal can be learned from tracking youth over time, especially concerning severity of psychotic symptoms and social impairment, as these are risk factors known in the scientific literature to predict conversion to schizophrenia spectrum disorders. If the early interventions and palliative care provided to these youth following the Consultation are effective in reducing risk for psychosis, these data will show the impact. These data and findings would contribute to the sparse knowledge and literature on early intervention in psychosis.

APPENDIX A

APPENDIX B

Host Companion

Host Companion