The Longlasting Psychological Effects of a Tragic Fire

by William Van Ornum, Ph.D. on

An anniversary passes, never to be forgotten

In early December a tragedy occurred, one causing untold sadness and posttraumatic stress disorder. Yet in the 56 years since this happened, signs of resiliency have also emerged.

In my mind’s eye, I can see my grandfather, 56 years ago, sliding down the chrome pole in his firehouse and landing on the rubber mat.

In our family and among the firemen, he was known as The Comedian. Once he told me he had been a general in the Army and gave me a small military pin. I believed him and told my teacher. When word of this got back to my father, he sat back as he roared, “Your grandfather wasn’t an Army general. He was a general nuisance!” But everyone loved him.

No doubt on that day, Monday, December 1, 1958, at 1:41 in the afternoon, he groused about one thing or another in the manner of firemen (they were all men then, today called firefighters) everywhere. “Can’t they at least hold these off until we finish eating?”

A few minutes later as their hook-and-ladder was speeding south down Pulaski Road, someone recognized that the address was that of a school. After that, everyone on that vehicle became their most somber and heroic selves. The truck increased speed, continuing another three or four miles, with my grandfather sitting in the cat-seat way in the back and helping to steer.

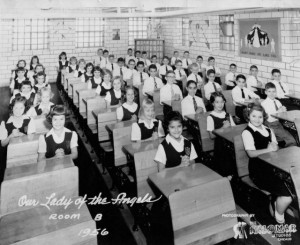

By the time they arrived at Our Lady of Angels School on Chicago’s West Side, probably half the Chicago fire department was there; in a few moments most of the city fire battalions would be on the scene.

Somehow a blaze had started in the school with the varnished-wood walls and floors. By the time the firemen arrived there were injured and dead children lying around. Although neighbors ran over with ladders, the windows were too high to reach, and the children jumped.

It is said that on that day firefighters rescued more people than would any other fire department before September 11, 2001: roughly 160. Yet an astronomical number of people died: 92 children and 3 nuns.

Many of those who died were killed by the smoke that billowed through the broken-glass transoms above the wooden doors. One sister had the children place clothing and towels around doorways to keep the smoke out. Most in this classroom survived.

In another room, Sister asked the children to pray. This is what they were doing when they were choked to death by the smoke or burned to death by the fire.

In one bit of sad irony, it was rule-breaking older boys who survived. When their teacher told them to stay in the room, they pushed her aside and ran out as quickly as they could. They survived.

To help everyone in the world remember this tragedy, the survivors and their families have contributed to a Web site (see below). The photos there are beyond the description of any words. The boy who started the fire was known to many survivors, but his name has never been released. Unlike modern tragedies that become associated with a perpetrator’s name, the Our Lady of Angels Fire continues to be about the children and nuns that died.

One of the survivors said, decades later, in To Sleep with the Angels by David Cowan and John Kuenster:

All I remember was this cloak of sadness. Everyone was sad. This was a sad neighborhood now. You had to be careful of who you were around, what you might say, what you might not say. How could a neighborhood survive that? It didn’t. People couldn’t face those who suffered. They couldn’t deal with it. They should have had support groups right then, immediately. They should’ve got those families together who was kids. They should’ve brought together these kids who were burned.

Seeing kids who were scarred – you never knew a person could be burned so badly and that they could be so disfigured. You didn’t even want to be around them, to look at them. Yet at the same time you wanted to because you never saw anything like this in your life. These little kids in uniform going to school, all scarred for life. (page 257)

Surprisingly, as Cowan and Kuenstler report, some of the children in the fire went into positions of responsibility wherein they would once again serve under battlefield conditions. One became a principal; another, a police officer who served on the front lines in a very tough city:

Despite several brushes with danger as a Chicago police officer, nothing Matt Plovanich has seen matches the peril he experienced as a 10-year-old boy trapped inside Room 207. He could recall precisely the look of utter terror that swept his nun’s face when she realized that the occupants of the ‘cheese box’ were trapped inside their tiny corner classroom. (266)

A fireman who had fought the fire provided his memories 34 years later:

We didn’t have masks in those days. We stayed up there in that smoke and that heat and we breached those walls. When we got inside, in those first two rooms on the North Side, that’s where we found a lot of kids, lining the wall and the floor below the windows.

They were all dead. In that first room they were piled up on the base around the nun’s desk. As we removed the bodies from the pile we noticed the children were not burned. They were asphyxiated. In the next room they were burned very badly.

The effort, the expenditure of energy to take down that wall was tremendous and then to have this hit you in the face, ‘Hey we’re too late. We are absolutely too goddam late.’

It was the worst fire I have ever been to, and I’ve been to some goddam bad ones. But nothing like that one. Never in my wildest dreams. (284-85).

I have always wondered what my grandfather did on that day. Of course, as was the culture, no one talked about it. But I remember him throughout the 1960s being one of the first to start to celebrate Christmas, in fact, usually around December 1. He devoted the entire month to seeking out presents for children both inside and outside the family. Among the toughest of men, he was one of the most gentle around children. Was this his way of remembering and grieving? I will never know.

Perhaps there will be a day when December 1 will be acknowledged in the Church as a Solemnity—In Remembrance of the Children and Nuns of the Our Lady of Angels Fire, their families, their neighborhood, their city, and very importantly all who displayed heroism to save them. Many became saints that day.

In 1958 there were no multimillion-dollar government grants to help the families or the neighborhood. It was even decades until a small memorial to the children was built.

Yet the families endured, touched by grace.

Their endurance may offer some consolation to others in similar situations.

On the 50th Anniversary of the OLA Fire, over a million hits were received on its Web site.

Host Companion

Host Companion