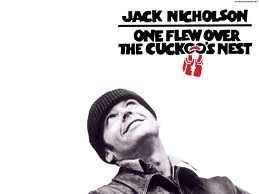

Psychiatry Films from AMHF: “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” (1975)

by Evander Lomke on

McMurphy (Jack Nicholson) as a wise-cracking Everyma

Of the twenty-one films for discussion on this Web site, here is number six, which stars Jack Nicholson and Louise Fletcher in signature roles.

Thus is the plot, in slightly condensed form, from Wikipedia:

In 1963, Randle Patrick “Mac” McMurphy (Jack Nicholson)—a recidivist anti-authoritarian criminal serving a sentence on an Oregon-prison farm for statutory rape of a fifteen-year-old girl—is transferred to a mental institution for evaluation. Although he does not exhibit overt signs of mental illness, he hopes to avoid hard labor and serve the remainder of his sentence in a more relaxed hospital environment.

McMurphy’s ward is run by sadistic Nurse Mildred Ratched (Louise Fletcher), who employs subtle humiliation, unpleasant medical treatments, and a mind-numbing daily routine to suppress patients. McMurphy finds that they are more fearful of Ratched than they are focused on living normally in the outside world.

McMurphy establishes himself as the leader among a group of players that would become household names in later years: the most important character being Will Sampson’s “Chief” Bromden, a mysterious Native Indian believed to be deaf and mute.

McMurphy and Ratched’s battle of wills escalates. McMurphy steals a hospital bus and herds his colleagues aboard, and they begin to feel stirrings of self-determination. Soon after, however, McMurphy learns that Ratched and the doctors have the power to keep him committed indefinitely.

Sensing a rising tide of insurrection among the group, Ratched tightens her grip. During one of her group-humiliation sessions, McMurphy and Chief wind up brawling with the orderlies, and are sent up to the “shock shop” for ECT

While McMurphy and Chief wait their turn, McMurphy discovers Chief’s secret: He is delirious to learn that Bromden is neither deaf nor mute, and that he stays silent to deflect attention.

After ECT, McMurphy shuffles back onto the ward feigning illness, before humorously animating his face and loudly greeting his fellow patients, assuring everyone that the ECT only charged him up all the more and that the next woman to take him on will “light up like a pinball machine and pay off in silver dollars.”

But the struggle with Ratched is taking its toll, and with his release date no longer a certainty, McMurphy plans a complicated escape with the others.

Nurse Ratched arrives the next morning and discovers the scene: The ward is upended. She orders the attendants to lock the window, clean up, and conduct a head count. Enraged at Ratched, McMurphy nearly chokes her to death until an orderly knocks him out.

Recovering from the injury sustained during McMurphy’s attack, Ratched wears a neck brace while the patients pass a rumor that McMurphy dramatically escaped the hospital rather than being taken “upstairs.”

Late that night, Chief Bromden sees McMurphy being escorted back to his bed, and initially believes that he has returned so that they can escape together. However, when he looks closely at McMurphy’s unresponsive face, he is horrified to see lobotomy scars on his (McMurphy’s) forehead. Unwilling to allow McMurphy to live in such a state, or be seen this way by the other patients, Chief smothers McMurphy to death. He then carries out McMurphy’s escape plan by lifting the hydrotherapy console off the floor and hurling the massive fixture through a grated window, climbing through, and running off into the distance.

The film is an adaptation of the satiric best-selling novel (1962) by Ken Kesey, a work that was overwhelmingly popular among high-school and college students by the 1970s. The book caught the anti-establishment Zeitgeist of the era via the free-spirited character of McMurphy—almost in the way Salinger caught the spirit of postwar America thro Holden Caufield, one who likewise has a familiarity with “the head-shrinker.”

An entertaining movie (nominated for nine Oscars and winner of five), Cuckoo’s Nest of course similarly has much to do with existential themes of conformity and nonconformity. More importantly, at a distance of nearly forty years from release, is the hideous depiction of the mental institution. This is far from Oliver Sacks’s Awakenings (though not specifically the setting of a mental institution). Filmed in a stylized, somewhat vulgar, and freewheeling manner to underscore its cynical hipness in targeting Baby Boomers (the primary audience on release), One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest also depicts a viciously dysfunctional, almost amoral form of group psychotherapy. One might fruitfully compare the depiction of Nurse Ratched with the idealized psychiatrists of Now, Voyager and Don Juan De Marco.

Like The Bell Jar, another important theme involves ECT as a modality of therapy. By comparison, one may look at one of our earlier blogs, a substantive interview with Alexandra Styron, regarding the experiences of her father.

In short, the clinical setting of One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest could not be more hell-like in this Hollywood depiction, even as re-created in The Snakepit.

Check out this New York Times article on similarities between movie sets and institutions: the real-life setting of One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Also, watch (below) the Salem, Oregon, place as it appears in one of the grimmer scenes from the movie.

Host Companion

Host Companion