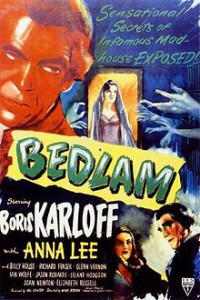

Psychiatry Films from AMHF: “Bedlam” (1946)

by Evander Lomke on

Legends Boris Karloff and Val Lewton team up

Have you ever felt that you were in hell? As the word pandemonium derives from John Milton’s Satan and his crew in Paradise Lost—in The Screwtape Letters C. S. Lewis refers to the environment/condition as “The Kingdom of Noise” (“the mind is its own place, and can make a heaven of hell and a hell of heaven” as Milton also says)—so bedlam has its origin in the UK: Saint Mary of Bethlehem Hospital, London.

This film, number twelve of the twenty-one under review in the AMHF series, is equal parts horror movie and social indictment. As such regarding the latter, it has elements in common with One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, The Snake Pit, and to an extent Charly; regarding the former, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

The time is 1761: the age of the Enlightenment. After an acquaintance, Lord Mortimer, dies in an attempt to escape from the asylum, apothecary general Master George Sims (Boris Karloff, a fictionalized version of an infamous head physician at Bethlem, John Monro) appeases Mortimer by having his so-called loonies put on a show for him. Mortified by the treatment of the patients, Mortimer’s associate Nell Bowen seeks the help of Whig politician John Wilkes to reform the asylum.

Mortimer and Sims conspire to commit Nell to the asylum, where her initial fears of fellow-inmates do not sway her sympathetic commitment to improving their conditions.

Frustrated by Nell’s progress with the inmates, Sims threatens her with his strongest “cure”; but his attempt is thwarted by the very inmates that Nell helped. Ultimately, Sims is literally “deposed” and Nell is rescued by her Quaker friend who had counseled her through the whole process.

So reads the Wikipedia synopsis of the plot in slightly reduced detail.

Val Lewton, a stylized and literate filmmaker with a cult following who was responsible for other off-center movies like Cat People (as producer), and was equally popular with RKO, for “working cheap” and quickly, as well as with audiences, is teamed with his star, Karloff—who was more than happy to throw off his Universal Studios-monster typecasting, albeit playing a part almost as macabre.

Readers of a certain generation will remember Geraldo Rivera’s uncovering of the horrors of Willowbrook. Serious mental-health disorders are a horror: for individuals relegated to “a madhouse”; families; friends. A modern-day visit to the CPEP Unit at one of the great hospitals in the world, Bellevue in Manhattan, or Creedmoor Psychiatric Center of Queens Village, shows the range of violence, self-inflicted as well as “other-inflicted,” which society confronts among those with disorders that can be treated, and those not well controlled. (There are many more drugs of choice and modalities of treatment than there were even a few decades ago; but so-called deinstitutionalization presents its own dilemmas.)

With these grim elements showcased in the film under review, albeit as a form of fright-entertainment, serious issues hit the viewer in the gut. We are hundreds of years removed from the Enlightenment. Yet, what are our present levels of tolerance and personal enlightenment? Walk thro NYC streets or ride its subway. There are screamers, self-talkers, the homeless: modern Bedlam, hell on earth. See also Titicut Follies, a documentary from 1966-67. Are we yet anywhere close to becoming a compassionate society?

Host Companion

Host Companion